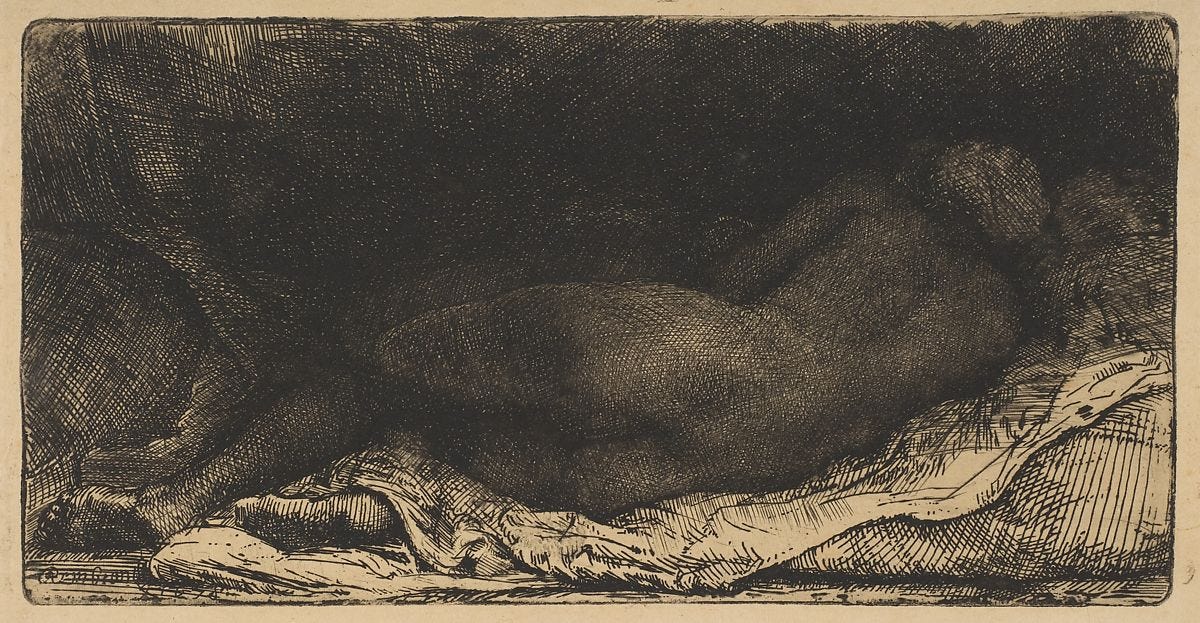

Reclining Female Nude, Rembrandt van Rijn (1658). Met Museum Collection.

Dear beloved,

I have been thinking a lot about how we teach young children about what matters.

I work in a school where everyday is a calculation of how to get kids to care about things. There is a fine balance to strike: come on too strong and you risk alienating them; resist the urge to punch the accelerator and you’ve lost them before we even approach the speed limit. There is also the problem of the infinitesimal number of things they could potentially give a shit about: literature, mathematics, physics, sports, art, world politics,

So when I approach a student, I always have to ask them and myself: how do I capture your interest in mathematics and keep it? How do I get you to sit down and listen to a lecture about dead kings and queens, the environment, literary devices — and more important, how do I get you to understand their relevance to your daily life? How can I get you interested in co-curricular activities geared towards shaping you towards a fullness of self, in the hopes you will emerge a whole, an Athenian miracle?

I’ve been feeling fortunate to have had the time and capacity to ask myself these questions because of the sharp turn the world has taken on the highway these last few weeks: How do I get you to care about anti-racism work? How do I get you to sit down and carefully read dense theory and argumentation about the toxicity and destruction wrought by systemic injustice — and how can you apply them in your daily life? How many resources do you actually want — or to put the point more finely, how many articles/books/podcasts do you really want to absorb, or are your questions about “where to start” just another form for performative allyship?

How can I get you interested in the distinct nuances of lives beyond your own, whose understandings can enrich your behaviour and appreciation of the inherent beauty and value of humanity?

Part of our struggle in school is trying to get kids to care about each other, alongside their schoolwork. When we all enter this world, we all belong to each other. We are responsible for one another, and we can all be better teachers.

the city atop a grave

I wasn’t too sure how to start this second (!!) edition of the newsletter. The very first I wrote was really about the tarot pulls for March — then it was going to be about some thoughts I had in the aftermath of some really lovely feedback regarding a piece of fiction of mine that got published in April. Then it was going to be about the lockdown and the ensuing drama-rama-ding-dong.

We’ve been saying for years that the news cycle is moving way too fast for us to keep up, but that feels truer than ever now. I doom-scroll late into the night and early in the morning.

So I’m settling on something un-tied to the news but informed by it nonetheless.

I am thinking a lot about whose bodies pay the price for our society’s broken systems: migrant workers, Orang-orang Asli, hospital cleaners, housewives, refugees, underpaid, the poor, the school-less, teachers, government doctors and nurses, the homeless, the disabled, LGBT folks — within this group, trans women whose existences exact higher tolls, payment made in death — Muslim women, girl-children-made-brides, survivors of sexual assault, garbagemen etc. As my friend Syar pointed out, the list could go on forever, and it still would be an imperfect accounting.

A View of Delft after the Explosion of 1654, Egbert van der Poel (National Gallery)

My point is that our cities and lives are built on top a mass grave of bodies.

And in those cities, in the glittering towers, it’s hard to ignore that the kinds of people who live in them: rich, largely white (but not always), deaf to begging and devoid of empathy. Largely men. Almost always men. Not always men, but also — always men.

I could make this all about all the different sub-groups that make up the Big Bads of our world, but I’d just like to talk about the men for a second. If you please.

I think a lot about men and the suffering they inflict on not just women (though, curiously, women are always the ones whose bodies pay the price) — but also on their children, their communities, the people around them, then their children’s children. You see, you can take a man and look at his unworked issues and you can trace it back to a legacy of other women and men who have been battered by an ancestral rot of toxic masculinity.

My father was hurt by his father, who in turn hurt his wife, who hurt her children and then her grandchildren and so the story goes — hard to find the source when the web gets all tangled, but there’s that old rag about Original Sin.

responsibility is cost men have avoided paying

The thing about hurt and harm is that it has been made necessarily transactional by a capitalistic economy and history. It doesn’t need to be this way, but it is how it has been built. Everything is by design.

You could say much of the injustice in the world are products of a system that has abetted the powerful and male (and a lot of the times, the white) in the avoidance of paying the tolls of harm. This could look like many things, but the clearest example is the enslavement of African peoples for labour.

I keep thinking about this line from one of my favourite podcasts, Still Processing: “white people are not ready to face the depths of black pain.”

It goes deep and it’s the wound of eternal loss. It is the same, somewhat, as the endlessness of Orang Asli pain, of losing home again and again and again, in a cycle of taking and losing — I think about migrant worker pain, of breaking your body everyday in heat and labour and hate. I think about women pain, of constantly paying the wages of a world run by men.

If we are serious about repairing brokenness, part of the transaction of harm for healing is the necessity of acknowledging the pain itself. It requires toll payments in fortitude and courage, humility and vulnerability — it requires decentering yourself from the conversation and a recognition that someone else’s pain is more important than your sense of comfort. It requires a dismantling of who you have believed yourself to be.

That’s The Work. That’s Life Work, that’s Pain Work — most of all, that is Healing Work.

And yet, the people who I consistently see Doing The Work™ are women and minorities. They excavate their trauma, dig deep into wounds and pour salt on the altar of forgiveness — they research and write and discuss and get angry and organise and volunteer and donate and give and give and give — and forgive and forgive and forgive.

(I often think that if just the women of the world were to pour our pain out into the earth — what more other marginalised and harmed communities — we would turn it bitter, make it barren for the rest of eternity).

Panel, designed by Sigmund Pollitzer, made by Pilkington Ltd, 1933 – 38, St. Helens, England. Victoria and Albert Museum, Art Deco Collection.

I have dated a number of men to whom the Hard Work stuff is just decoration. It’s wallpaper. Too much Brené Brown will rot your brain, they seem to say. Read “Becoming”? No, thank you! Seek therapy? I think not. Take responsibility for the harm and hurt I have inflicted on not just myself but the other people in my life because I refuse to face the scalding truth that I am capable of wounding people and that fact scares me? I’ll pass.

I don’t need to date someone broken to know that so many of the men in my life, and those who I know of peripherally, have a real problem with being accountable for their actions. I am not surprised, after all, because what in society has ever taught them that they need to be responsible for their actions? Isn’t every lever in society geared towards ensuring men never have to be accountable to anyone but themselves?

The patriarchy ensures that men remain in power because the patriarchy itself is borne out of a transactional market where the wages are the pain of other people. White patriarchy is built atop the violated bodies of enslaved people, of black and brown people.

When we say “toxic masculinity hurts men as much as it hurts women”, we mean it — I have seen men make horrifying choices that not only directly affect the their victims, but which breed fear and revulsion at the self because its hard to fathom that you can be this cruel, be this chaotic, be this destructive. Masculinity — something that could be beautiful, could be generative — has become something to fear.

So: whose bodies pay the price?

Even when men make horrifying choices, it’s the women around them who are apologising on their behalf: the victims, the friends, the acquaintances, the work colleagues. All women.

“I’m sorry I did not know.”

“I’m sorry I uplifted his work.”

“I’m sorry I defended him.”

“I’m sorry we worked on a project together.”

“I’m sorry I can’t be sorry enough to fix this.”

A Greek chorus of apologies on behalf of the man. Always for the men.

I am terrified for the men in the world. I am terrified of the inhumanity they have bred into not just themselves, but the numbness they reinforce in their peers, the disregard they will pass down to their sons as inheritance. I am fearful of their inability to claim responsibility for anything they do.

Table for Ladies, Edward Hopper (1930). Met Museum Online Collection.

generations work

I cannot give you easy answers or fixes to this. The project of building a world that is better than the one we currently live in is a project of Hard Work, and it cannot be done if the people who most benefit from ignoring other people’s pain refuse to get involved. If they only ever act defensive when their faults and harms are pointe out.

How do you account for a lifetime of pain? How do you fix the eternal wounds of trauma? How do you pay that back? How do you measure its depths, its height and weight and width, then calculate out a price?

You cannot.

You can only acknowledge it, and attempt to repair the gaping wound. There are so many bodies that have been strewn across the threshing floor of history — women’s bodies, black and brown bodies, the bodies of children, bodies between genders and bodies beyond the binary, disabled bodies, poor bodies, homeless bodies, forgotten and murdered bodies — that accounting for them all is Generations Work.

But we also must remember that accounting for those bodies is also Heart Work. Remembering their names, redistributing our wealth and time and energy to fund the market with something else other than pain.

It is Generations Work to teach this to children, to our friends and family. But most importantly, it’s Generations Work to learn these lessons and embed them deep in your soul. Learn it and use it as a lens through which to reshape this world.

So start here: if you have harmed someone, just take a second and acknowledge their pain. Ignore that niggling feeling inside you that wishes to get defensive and angry, that wants to not have to pay this tax — write down what you might owe them, and figure out how you can make it right. Maybe it is simply saying, “I owe you money. How much?” Maybe it is accepting the horror of your own humanity, and apologising for it.

Most of all, learn to accept responsibility. We belong to each other.

Love to you from the void, always,

Sam.

resources

I have been thinking about two pieces of writing during this time: Adam Serwer’s “The Cruelty is the Point” (The Atlantic) and Kayla Chadwick’s “I Don’t Know How To Explain To You That You Should Care About Other People” (The Huffington Post)

My friend Syar’s Record of a Year newsletter on “Harm and Healing Within Communities” is making the rounds, rightly so for it’s incisive, compassionate and generative resources on addressing harm and healing communities through collective action — but it’s her second June 2020 piece, on the Threes in the Minor Arcana which made my heart ache with sorrow and joy.

Thank to this thread by Syar and @uu1iu, who are Doing The Work by responding to the miasma of sexual abuse that has permeated Twitterjaya. We started working on a Carrd resource for survivors and allies, which I will tweet out later. Translations in Tamil and Mandarin are forthcoming.